Dior + Balenciaga: The Kings of Couture and Their Legacies

“Dior and Balenciaga were not only the most important and influential couturiers of their time, they have also remained very relevant today,” says Patricia Mears, deputy director and curator of the exhibition.

Dior + Balenciaga: The Kings of Couture and Their Legacies featured fashions by the two most important couturiers of the mid-20th century, Christian Dior (1905–1957) and Cristóbal Balenciaga (1895–1972). Featuring approximately 65 garments and ensembles drawn solely from The Museum at FIT’s permanent collection, it was the first exhibition to juxtapose the work of these legendary designers, side by side.

VIEW OBJECT AND INSTALLATION IMAGES IN THE ONLINE COLLECTIONS

Unlike recent large-scale retrospective monographic exhibitions of the two designers, Dior + Balenciaga: The Kings of Couture and Their Legacies was an intimate, curatorial exploration and reevaluation of their work. The focus was on their innovative construction methods and the exquisite workmanship of their respective ateliers.

Although their backgrounds and methodologies were markedly different, Dior and Balenciaga concurrently produced fashions that captured the era’s hunger for luxury and elegance and led the restoration of France’s profitable fashion industry after the devastation of two world wars and a crippling economic depression. Together, they contributed to France’s economic and cultural recovery, both launching their eponymous collections at age 42.

"Dior and Balenciaga were not only the most important and influential couturiers of their time, they have also remained very relevant today," said Patricia Mears, deputy director of MFIT, and curator of the exhibition. "So much so that contemporary fashion designers regularly look to them for inspiration. It is also the reason why curators and historians around the world continue to organize many large-scale exhibitions and produce lavish books celebrating their creations."

Dior’s work was noted for its focus on the sensuous female form. He was not a dressmaker but, rather, an illustrator who worked closely with the skilled artisans of his ateliers to bring his designs to fruition. A self-described reactionary, Dior strove to banish the deprivation of the war years; he modernized the corseted shape of the Belle Epoque, a glorious period for which he remained nostalgic throughout his life. Charming and eloquent, he was described by Cecil Beaton as a "bland country curate made of pink marzipan." Yet, Dior was also a savvy businessman whose company accounted for more than half of France's couture exports during the 1950s.

Christian Dior, ivory silk satin evening dress with silk and metallic embroidery, possibly by Rébé, Spring/ summer 1954, "Muguet" Line, gift of Despina Messinesi, 75.86.5

Christian Dior, ottoman silk, 1952, gift of Julia Raymond, 77.144.1.

Christian Dior, silk and synthetic tulle evening dress; assorted sequins, paillettes, beads and ribbons, embroidery by Rébé, Autumn 1957, gift of Harriet Weiner, 73.35.9

Balenciaga was hailed by fashion journalists and fellow creators as the greatest dressmaker in the world. Dior referred to him as “the master of us all.” Despite his mastery of couture, Balenciaga hailed from a humble Basque fishing village, began practicing his craft as a youth, and opened his business when he was a young man in his native Spain. Then, during the Spanish Civil War, he bravely expanded by moving to Paris in his 40s, where he became an internationally renowned couturier.

Cristóbal Balenciaga, sleeveless "sack" dress, tan slubbed silk, Autumn 1957, gift of Beth Levine, 77.27.2

Cristóbal Balenciaga, cocktail dress, blue silk and lace by Marescot, 1957, gift from the Estate of Tina Chow, 91.255.1

Cristóbal Balenciaga, evening gown, green and yellow printed silk taffeta by Abraham, 1961, Eisa label, Spain, gift of Margay Lindsey, 83.159.1

Dior exquisitely crafted dresses built upon corsets and crinolines and Balenciaga brilliantly constructed voluminous coats and dresses. Viewers may have been surprised to see remarkable similarities in some of the pairings, making immediate attributions less obvious. The couturiers' shared vocabulary were seen in the juxtaposition of three pairings of garments in the introductory gallery: black dresses with asymmetrical buttons, boxy day suits, and voluminous evening dresses. Without looking at the labels, visitors may have found it difficult to guess which designer created each garment—Balenciaga or Dior?

The exhibition also presented numerous ways in which the two couturiers constructed garments differently from one another. For example, two beige silk evening dresses positioned at the gallery entrance were similar in color, fabrication, and silhouette. Balenciaga was a master couturier who crafted the volume and fullness of the skirt through the deft handling of fabric. Dior, by contrast, had to rely on built-in corsetry and layered underskirts to achieve volume. The weight of each dress also denoted their differences: the Balenciaga gown is only 2.2 pounds while the Dior garment weighs over 9 pounds.

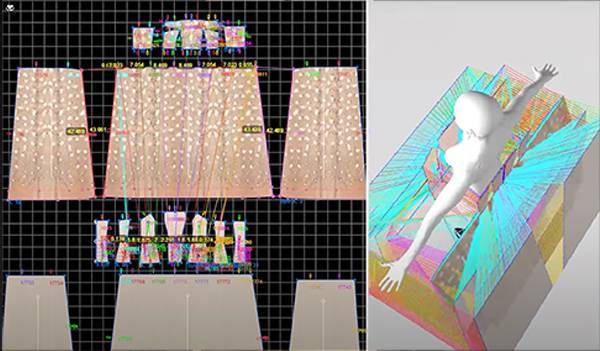

Accompanying several key objects from MFIT's permanent collection—including an embroidered evening dress by Dior and a "sack dress" by Balenciaga, both from 1957—were educational components such as muslin reproductions, videos, and digital patterns that illustrated the complexities of haute couture construction. These components were created by Tetsuo "Ted" Tamanaha, an assistant professor of Fashion Design in the School of Art and Design at FIT and also a theatrical costumer, couturier, tailor, and patternmaker.

To illustrate the continued impact of Dior and Balenciaga, approximately one-third of the exhibition included designs by other couturiers and some of the subsequent creative directors of the fashion houses they founded. The legacies of these venerated masters carry on, thanks to the artful blending of iconographic elements of the founders with contemporary trends.

The Dior aesthetic was carried on and expanded by Yves Saint Laurent (1957–1960), Marc Bohan (1960–1989), John Galliano (1996–2011), and, most recently, Maria Grazia Chiuri (2016–present).

Hubert de Givenchy did not work for Balenciaga. However, he and two of the label's creative directors, Nicolas Ghesquière (1997–2012), and Demna Gvesalia (2015–present), are among those who absorbed and renewed ideas pioneered by Balenciaga.

An intimate, curatorial exploration

In the Press

Talk and Tours

Dior and His Decorators: Victor Grandpierre, Georges Geffroy, and the New Look

Examining Haute Couture Construction Techniques with Technology

Tetsuo "Ted" Tamanaha, assistant professor of Fashion Design in the School of Art and Design at FIT, not only studied Balenciaga and Dior's innovative construction techniques by creating replicas in muslin, but he also created digital patterns and rendered them on 3D avatars to illustrate the garments in motion. Together, the muslin reproductions, digital patterns, and 3D simulations highlight the complexities of haute couture construction. These educational components accompany the garments themselves and are on view in the exhibition and online.