Power Mode: The Force of Fashion

Today, we see a multitude of sartorial power symbols, from "power suits" to "power heels." But what makes a garment "powerful"? According to sociologist and political theorist Steven Lukes: "We speak and write about power, in innumerable situations, and we usually know, or think we know, perfectly well what we mean ... And yet, among those who have reflected on the matter, there is no agreement about how to define it, how to conceive it, how to study it, and, if it can be measured, how to measure it."

<< Share using #PowerMode on Twitter and Instagram. >>

Reebok by Pyer Moss Collection 1, fall 2018. Photo courtesy of Pyer Moss shot by Maria Valentino.

Christian Dior by Maria Grazie Chiuri, spring 2017. Photo firstVIEW.com.

Chanel, Karl Lagerfeld, shoes, cruise 2009, France, gift of CHANEL, 2012.63.1

If we think of power in terms of kinetic force (for example, electrical power or a person’s physical power over another), clearly an inanimate item of clothing does not have actual power. The force of fashion is symbolic. It is social. It lies in the sphere of interpersonal relations and cultural dynamics. There is no single, universally accepted definition of power. Power means different things to different people at different times. As such, its connection to fashion is multifaceted, and a multifaceted approach is necessary for considering the role fashion plays in power dynamics both historically and today.

The exhibition was organized into five thematic sections, each devoted to a particular type of sartorial "power." In each section, men’s and women’s clothing were considered side by side, and pieces from as early as the eighteenth century were juxtaposed with looks from contemporary collections.

The first section considered military uniforms and their transformation into fashion items. Modern military uniforms combine tailoring with an elaborate code of patches, braiding, stripes, colors, and metalwork that makes the solider a walking extension of the state’s power. In fashion, a company logo replaces the state’s seal, but uniform-inspired silhouettes, colors, textiles, buttons, etc., become visual shorthand for the power, strength, and authority of the military. It is the power of association.

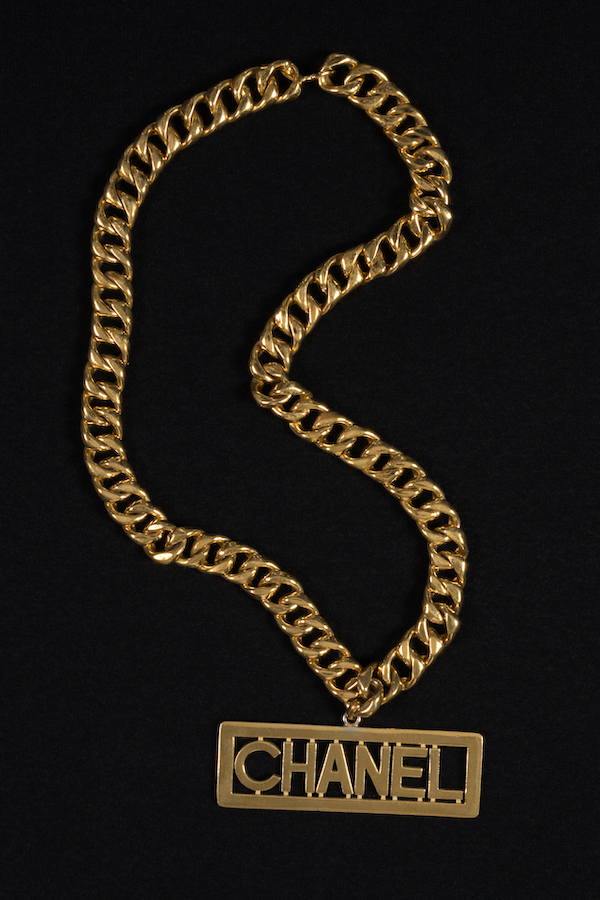

The second section looked at status dressing from ermine capes and luxurious brocade fabrics to contemporary "It" bags and logo-covered products. Wealth and class are key to understanding the role status dressing plays in modern society as are issues of taste. In 1899, Thorstein Veblen laid out his theory of "conspicuous consumption" to highlight the performance in owning and displaying status goods. While status dressing was once reserved for monarchs and aristocrats, today Peter McNeil and Giorgio Reillo observe that "consumers think that luxury is something that everyone should aspire to." This is the paradox of contemporary status dressing — accessible luxury.

The exhibition opened with a display of military and military-inspired ensembles, including a U.S. Army lieutenant colonel’s "dress blue" uniform, a World War II–era "Ike" jacket, and looks from Yves Saint Laurent, Burberry, and Ralph Lauren. Modern military uniforms combine tailoring with an elaborate code of patches, braiding, stripes, colors, and metalwork that makes the soldier a walking extension of the state’s power. In fashion, a company logo replaces the state’s seal, but uniform-inspired silhouettes, colors, textiles, and buttons become visual shorthand for the power, strength, and authority of the military. It is the power of association.

The next section focused on different modes of status dressing that have emerged over the last 250 years, from ermine capes and luxurious brocade fabrics to contemporary "It" bags and logo-covered products. Aspiration, wealth, and Thorstein Veblen’s theory of "conspicuous consumption" are key to understanding the role status dressing plays in modern society. An 18th-century robe à la française demonstrates the importance of ornate, expensive textiles to courtly dress, while a Balenciaga puffer coat shows the way brand names have become crucial decorative elements in luxury fashion today.

Robe à la française, 1760-1775, USA, museum purchase, 2017.2.1

Chanel, Karl Lagerfeld, necklace, fall 1991, France, gift of Depuis 1924, 2013.56.1

Vetements, Demna Gvasalia, T-shirt, spring 2016, France, museum purchase, 2018.46.1

From status dressing, the exhibition moved to consider the history of the suit. The sharply tailored suit is perhaps the most conventional example of "power dressing." Indeed, the term power dressing was often used to describe the big-shouldered suits worn by upwardly mobile business men and women during the 1980s. However, the history of the suit is more nuanced. Anne Hollander points out, "Heads of state wear suits … and men accused of rape and murder wear them in court to help their chances of acquittal." In court rooms and office spaces, the suit isn’t just a symbol of authority. It is also a sign of blending in — submitting to established norms and dress codes.

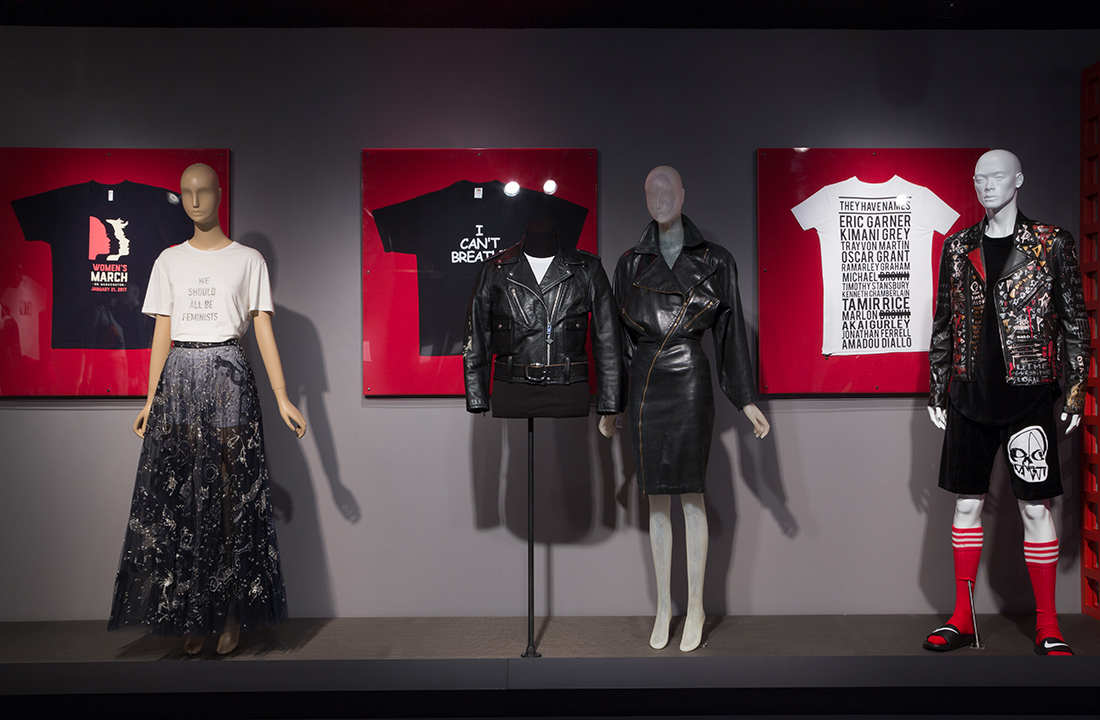

The next section considered the role of resistance dressing. Blue jeans, printed T-shirts, and black leather jackets have become some of the most common symbols of resistance in clothing. They signal a certain type of power that is subversive of established authority. It is the power of protest and rebellion. There is a tension between resistance clothing and "fashion," with the later often being dismissed as surface-level commodification. But the relationship is not so simple — fashion can also be a vehicle for protest as seen in the recent work of Kerby Jean-Raymond for his label Pyer Moss.

Off-White, Virgil Abloh, "Hoodie" sweatshirt, fall 2018, Italy, gift of Off-White, 2019.8.1

"Pussyhat," 2017, USA, gift of Colleen Hill, 2018.14.1

Shorts, circa 1970, USA, gift of the Nancy Hariton Gewirz Collection, 2016.20.3

Finally, the fifth section analyzed objects associated with sex and sexuality. There are many fashion objects that are culturally coded as "sexy." Corsets, leather, lingerie, and high-heeled boots are but a few examples. The power dynamics of these garments are inherently complex. How a garment is interpreted can fluctuate between dominance and subjugation. As fashion critic Holly Brubach once said of Versace’s famous 1992 bondage collection, it "riles women who think this is exploitative and appeals to women who think of his dominatrix look as a great Amazonian statement. It could go either way." Power Mode was a curatorial experiment. It aimed to combine theory with history and object analysis in order to better understand the complex nature of power in fashion as well as the ways fashion can be key to a broader understanding of power dynamics in culture.

The Publication

A more in-depth discussion of the themes represented in the exhibition are articulated in the lavishly illustrated accompanying book, also titled Power Mode: The Force of Fashion, edited by exhibition curator Emma McClendon and published by Skira. The book delves deeper into theory and history to investigate how certain garments have come to be culturally associated with power, as well as how their meanings have evolved over time. It also examines how fashion designers have interpreted these stylistic archetypes — both to convey and to subvert power.

Chapter texts by McClendon are joined by object-based essays from renowned fashion scholars Valerie Steele, Christopher Breward, Jennifer Craik, and Peter McNeil, as well as Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Robin Givhan. The book also includes an essay by Kimberly M. Jenkins on the intersection of race, fashion, and power. This collection of texts offers readers a variety of perspectives to help form a theoretical framework for considering the power dynamics inherent in fashion objects.

Power Mode: The Force of Fashion was organized by Emma McClendon, associate curator of costume.

![]()